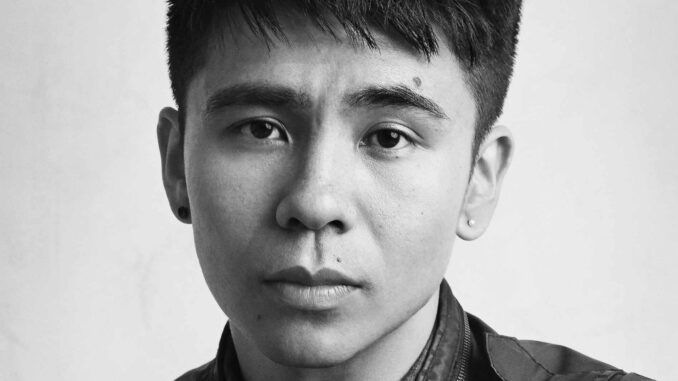

A SECOND CHANCE ON THE MARGINS: OCEAN VUONG’S THE EMPEROR OF GLADNESS IS A RADIANT EVIDENCE TO RESILIENCE, KINSHIP, AND THE STORIES WE TELL OURSELVES TO SURVIVE

(Introduced by Vo Thi Nhu Mai)

In his sweeping new novel, The Emperor of Gladness, Ocean Vuong, MacArthur fellow, former fast-food worker, and one of the most luminous voices in American letters, returns with a work that is as intimate as it is epic. Following the thunderclap success of On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Vuong’s second novel takes a courageous leap further into the human condition, writing from the edges of American life but speaking directly to its core.

Set in the crumbling, post-industrial town of East Gladness, Connecticut, a place as forgotten by policy as it is rich with ghosts, the novel opens in cinematic slowness: a nineteen-year-old Vietnamese American boy named Hai stands on the edge of a bridge, soaked in rain, poised to leap. His life is fractured, tender, shaped by addiction and abandonment. But in a moment of eerie grace, he is interrupted by the voice of Grazina, an 82-year-old Lithuanian widow succumbing to dementia, calling to him across the water. What follows is a narrative that resists convention and embraces messiness. Grazina takes Hai in, not as a saviour, but as someone in need of saving herself. Over the course of a year, they become a makeshift family, navigating the jagged terrain of memory, aging, grief, and care. It is not sentimental. It is not easy. But it is transformative.

For readers from immigrant or diasporic backgrounds, The Emperor of Gladness may feel eerily familiar. Vuong doesn’t merely write about assimilation; he writes about what it means to live in the “in-between”, not fully claimed by the country you’ve arrived in, nor fully intact from the one you’ve left behind. Hai is not a hero. He is not fully healed by love or saved by kindness. He remains vulnerable to addiction, to rage, to the weight of inherited trauma. Grazina, too, is not a saint. She hoards pain like photographs, forgets important truths, and clings to rituals like eating frozen Salisbury steak every night. But in their co-dependency, a strange form of care takes shape, one that doesn’t promise redemption but insists on connection. This is the heart of Vuong’s project: to show that belonging is often something we build ourselves, from wreckage and longing, and that the families we make can be as profound, if not more so, than the ones we’re born into.

At one point, Hai takes a job at a fast-casual diner chain called HomeMarket, flipping synthetic meals next to vats of unnaturally coloured side dishes. Here, Vuong’s prose turns observational, almost documentarian. We meet BJ, a would-be pro wrestler; Russia, a Tajikistani dishwasher with a haunted gaze; and Maureen, a conspiracy theorist cashier who self-medicates with frozen mac and cheese. These characters, while odd and sometimes grotesque, are not caricatures. They are rendered with generosity, humour, and depth. Through them, Vuong offers a subtle critique of American labour: the indignity of minimum wage, the corporatization of nourishment, the violence of invisibility. But beyond critique, The Emperor of Gladness is a novel about survival. It’s about the working class not as a demographic but as a poetic and moral subject. In Vuong’s hands, even a dingy HomeMarket shift or a trip to a slaughterhouse becomes sacred, tragic, and strangely beautiful.

Vuong is first and foremost a poet, and that muscle is never dormant. From the very first page, the prose sings: Ghosts rise as mist over the rye across the tracks… Such lines ripple with lyricism, but what makes Vuong unique is his ability to blend that lyricism with cinematic pacing. The bridge scene, the slow-motion collapse of Grazina’s memory, the hallucinatory climax in a wrestling bar, they all read like reel and verse, like Cormac McCarthy by way of James Baldwin and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. What’s new in this book, however, is Vuong’s comfort with plot. The Emperor of Gladness embraces narrative momentum without sacrificing stylistic complexity. The novel’s structure is looser, less recursive than his debut, allowing the characters to stumble, grow, and contradict themselves in real time.

Perhaps the most radical idea in The Emperor of Gladness is not in what happens, but in how the characters imagine their way through what happens. Hai invents calming roleplay games to help Grazina navigate her dementia. He fabricates stories for himself too—of a future where he might be sober, where his cousin Sony might be safe, where his mother’s anger might finally make sense. In one scene, Hai observes: Any economic aspiration at all is so clearly a fiction. But Vuong doesn’t mock this impulse. He elevates it. Everyone in The Emperor of Gladness is writing their way out of suffering, out of silence, out of structures not built for them. And in doing so, they’re not escaping reality, they’re reshaping it. For Vuong, imagination is not delusion; it’s resistance. Hai’s storytelling is an act of agency in a world that routinely strips people like him of control. When institutional systems fail, rehab centres that dehumanize, bureaucracies that entangle rather than support, families fractured by displacement and trauma, what remains is the fragile, powerful act of narrative.

Grazina’s dementia, for instance, is not just an affliction but a catalyst for collective reinvention. As she slips between temporalities and selves, Hai joins her, not out of denial, but out of love. Their shared hallucinations playing at being spies, artists, or inventors aren’t mere fantasies; they’re bridges across neurological and generational gulfs. The improvisational games they play recall the diasporic improvisation so central to the Vietnamese American experience: how do you become someone in a language that doesn’t always say your name right? The novel suggests that such storytelling isn’t just therapeutic, it’s infrastructural. Vuong’s characters build worlds with words because the material one offers so few spaces for them to be whole. The “fiction of economic aspiration” that Hai mentions isn’t a cynical dismissal, but an acknowledgment that even capital, even nationhood, runs on narrative. So why shouldn’t the wounded, the queer, the grieving, the undocumented write their own myths too?

Vuong interlaces these private inventions with lyric interludes, snatches of poetry, song, even footnotes that seem to belong to a separate narrator entirely. These moments rupture the text’s realism, not to obscure it, but to deepen it. Like the works of Toni Morrison or Arundhati Roy, Vuong’s novel insists that the truth is rarely linear or singular. There is no one story of survival, but many overlapping drafts—each trying, in its own syntax, to say: I was here. I mattered. What emerges is a poetics of care as much as resistance. In The Emperor of Gladness, storytelling becomes a form of mutual holding. A queer cousin cares for an aging woman cast off by her family. A trans narrator tends to language that has so often bruised them. Memory, unreliable as it is, becomes a communal project, rebuilt daily, lovingly, against erasure. And so the radical heart of Vuong’s novel beats not in its tragedies, but in its tender, fugitive joys. A birthday cake made from cassava and silence. A late-night phone call that sounds like music. A made-up story that saves a life, just for one more day. To imagine is to survive. To tell the story, even an invented one, is to refuse disappearance. In The Emperor of Gladness, Ocean Vuong shows us that fiction can be the truest form of presence.

In The Emperor of Gladness, storytelling is not a luxury but a lifeline, a means by which the marginalized characters hold onto coherence in a world that repeatedly threatens to unmake them. Hai’s invented futures, Grazina’s disoriented reenactments, and the narrator’s shifting registers of prose and poetry all form a latticework of resistance against the fragmenting forces of trauma, poverty, addiction, and exile. These aren’t merely narratives of escape; they are blueprints for survival, fragile but fiercely imaginative architecture built in the ruins of war, displacement, and generational silence. Vuong doesn’t simply document the damage, he tunes our attention to the quiet, deliberate ways his characters reassemble themselves, with memory as thread, language as glue, and love as scaffolding. There is sorrow in these pages, but it is never static; it flickers and folds into moments of improbable connection: a trans cousin bathing an elder with dementia, a cassette tape ferrying a lullaby across an ocean, a lie told not to deceive but to comfort. In this porous space between truth and fiction, Vuong restores narrative to those who have too often been denied one, offering not closure but a pulse, a continuing, trembling possibility. And it is in that shimmering, multi-voiced pulse that the novel speaks most clearly in the voice of multicultural literature: one that resists erasure, embraces hybridity, and insists that stories born from fracture are not broken, but vast.

(reference source: online)

📘 The Emperor of Gladness – Study Guide

Appendix & Glossary of Cultural and Literary References

1. Ocean Vuong:

Vietnamese-American poet and novelist (b. 1988, Saigon). Real name: Vương Quốc Vinh. Known for poetic prose and explorations of migration, war, gender, memory, and family.

2. George Bailey / It’s a Wonderful Life

Main character of the 1946 film It’s a Wonderful Life — a symbol of hope and redemption. The novel opens with Hai standing on a bridge, echoing George’s iconic scene.

3. Clarence the Angel

A guiding angel in the same film. In Vuong’s novel, Grazina becomes Hai’s “angel,” helping him rediscover the will to live.

4. Grazina

A Lithuanian female name. Symbolizes trauma and resilience — an elderly immigrant with dementia and humor, survivor of Stalin-era persecution.

5. Labas

Means “hello” in Lithuanian. Grazina uses this warmly but eccentrically due to her dementia.

6. East Gladness

A fictional town in Connecticut. Its ironically cheerful name contrasts with its economic decay — a metaphor for post-crisis America.

7. Stalin’s Purges

Refers to the 1930s Soviet terror under Joseph Stalin, during which millions were executed or exiled. Grazina’s background draws from this trauma.

8. HomeMarket

A fictional “fast casual” restaurant representing the modern American service economy. A convergence point for marginalized, low-wage workers.

9. Fast Food Nation (2001)

By Eric Schlosser. Investigative nonfiction exposing the fast food industry’s exploitation and environmental harm — a thematic parallel to HomeMarket.

10. Nickel and Dimed (2001)

By Barbara Ehrenreich. A journalistic exploration of working-class struggle in America. Highlights the precarity of low-income laborers, like characters in Vuong’s novel.

11. “The Office”

A U.S. TV sitcom about mundane office life. Used metaphorically in the novel to represent humor, futility, and the banality of labor.

12. Wallace Stevens

Modernist poet based in Connecticut. Known for surreal, abstract work. Vuong’s title may echo Stevens’ poem “The Emperor of Ice-Cream.”

13. Siddhartha Mukherjee

Author of The Emperor of All Maladies, a history of cancer. Vuong’s novel title may also allude to this, blending literary and medical metaphors.

14. Hai

A common Vietnamese name meaning “two.” or “ocean” Symbolizes duality — between cultures, generations, past and present, life and death.

15. “Sugar is the opiate of the masses”

A satirical riff on Karl Marx’s quote. Critiques how modern society replaces spiritual belief with consumerism and processed indulgence.

16. Slaughterhouse-Five / The Brothers Karamazov

Hai reads these classics during emotionally barren times. The gap between intellectual engagement and grim reality is a recurring theme.

17. Tetris

Addictive puzzle game. Hai’s mother plays obsessively — a metaphor for the repetitive, numbing cycles of immigrant life and trauma suppression.

18. Medicare

U.S. federal health insurance for the elderly. The novel notes a misconception: Medicare doesn’t cover in-home nurses, exposing gaps in the American care system.

19. Ted Lasso

A feel-good TV show known for kindness and optimism. Vuong subtly critiques its forced positivity by weaving its dialogue into darker contexts.